When it comes to cataract surgery in eyes with a history of uveitis, things can get a little more complicated than usual. You’re not just dealing with a cloudy lens—you’re navigating a landscape shaped by inflammation, immune responses, and a heightened risk of complications. But that doesn’t mean a successful outcome isn’t possible. With the right strategy—before, during, and after surgery—you can give these eyes a fair shot at clear, comfortable vision.

In this article, we’re going to unpack the latest evidence-based strategies that ophthalmologists use when approaching cataract surgery in uveitic patients. From pre-op inflammation control to picking the right intraocular lens (IOL), and keeping a close eye on things after surgery, we’ll walk through it all. Whether you’re a surgeon, a trainee, or even a patient trying to better understand your options, this deep dive will equip you with up-to-date, practical insight.

Understanding the Uveitic Eye

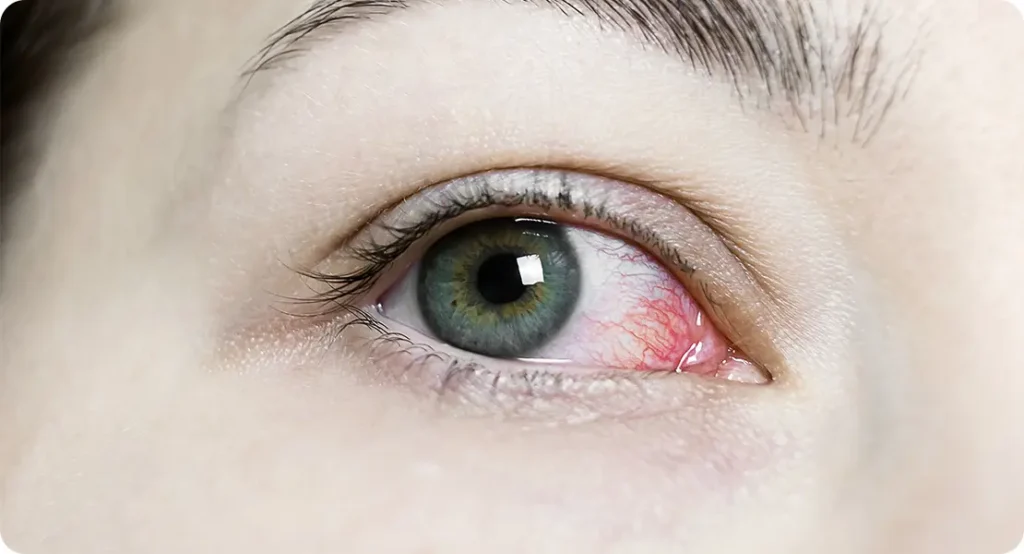

Let’s start by defining the terrain. A uveitic eye is one that has experienced inflammation in any part of the uvea—the middle layer of the eye which includes the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. This inflammation might be from an autoimmune condition, an infectious cause, or even idiopathic in nature. But regardless of the underlying cause, uveitis can lead to cataracts either through the inflammation itself or due to prolonged corticosteroid use—sometimes both.

These cataracts tend to develop earlier in life compared to age-related types. They also behave differently: the lens may become fibrosed, the zonules can be weak, and there’s often a higher risk of posterior synechiae (where the iris sticks to the lens). All of this means standard cataract protocols might not apply—at least not without some thoughtful adaptation.

Why Outcomes Are More Complex

Surgical outcomes in uveitic eyes have come a long way, but they still carry more risk than non-uveitic cases. You’re more likely to encounter problems like cystoid macular oedema (CMO), secondary glaucoma, or chronic inflammation post-op. Visual prognosis can also be affected by pre-existing macular damage, optic nerve involvement, or persistent uveitis.

But here’s the good news: with a proactive and multidisciplinary approach, many of these risks can be mitigated. Surgical advances, anti-inflammatory regimens, and careful postoperative monitoring have significantly improved the odds.

Pre-Operative Inflammation Control

This is perhaps the most important stage of all. A quiet eye before surgery lays the foundation for everything that follows. The general rule of thumb is that the eye should be inflammation-free for at least three months before proceeding to cataract surgery. But let’s break this down a little further.

Systemic and Local Therapy

Patients may already be on systemic corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents, depending on the type and severity of their uveitis. If not, this is the time to consult a uveitis specialist or rheumatologist. Oral steroids might be increased temporarily pre-op, or intravenous methylprednisolone may be used in more severe cases. Topical steroids are typically ramped up in the weeks leading to surgery.

Intravitreal steroid injections or implants—like dexamethasone (Ozurdex)—can also be considered in particularly difficult cases. The key is suppressing inflammation without tipping the scales toward steroid-induced IOP elevation or infection risk.

Pre-Surgical Assessment

Pre-op imaging like OCT and fundus photography can help identify hidden problems such as macular oedema or chorioretinal scarring that might influence surgical planning and prognosis. Likewise, synechiae should be mapped out and addressed where possible to avoid intraoperative surprises.

Intraoperative Considerations

Surgery in a uveitic eye often requires more than the standard phaco playbook. Here’s how surgeons optimise outcomes:

Managing Synechiae

Posterior synechiae can severely restrict pupil dilation, making access to the cataract difficult. Synechiolysis (breaking the adhesions) can be done manually, or through viscodissection. If the pupil remains small, iris retractors or Malyugin rings may be necessary to create a functional surgical field.

Phacoemulsification Strategy

A gentle hand is vital here. Uveitic eyes are more prone to intraoperative miosis and capsule rupture, so minimal ultrasound energy and a slow, controlled technique are crucial. Using dispersive viscoelastics can help protect the corneal endothelium and stabilise the anterior chamber.

If the zonules are weak, capsule support devices like capsular tension rings (CTR) may be required. These can maintain a round, centred capsular bag and improve long-term IOL stability.

Use of Intracameral Medications

Some surgeons administer intracameral steroids at the end of the case—usually triamcinolone acetonide—as an added layer of inflammation control. Others may opt for intracameral antibiotics if there’s concern about infection risk in an immunosuppressed eye.

Choosing the Right IOL

This is a big decision in uveitic eyes, and one that directly impacts long-term visual outcomes. Not all IOLs are created equal in this context.

Acrylic Over Silicone

When choosing an intraocular lens (IOL) material for a patient with uveitis, the decision can have long-term consequences for ocular health and visual clarity. Acrylic IOLs are widely regarded as the safer option for this group, primarily due to their inert properties. They tend to induce significantly less postoperative inflammation than silicone lenses. This is a critical consideration in uveitic eyes, which are already predisposed to exaggerated inflammatory responses that can escalate into serious complications if not carefully managed.

Hydrophobic acrylic lenses, in particular, are often the go-to choice for ophthalmologists treating uveitic patients. These lenses are less likely to attract inflammatory cells or protein deposits, which helps maintain clarity within the visual axis. They also have a lower incidence of posterior capsule opacification (PCO)—a common complication where residual lens epithelial cells proliferate behind the lens, clouding vision. Minimising this risk is especially important in uveitis patients, who may already be at risk of compromised vision due to macular oedema or optic nerve inflammation.

In contrast, silicone lenses are generally avoided in this setting. Their surface tends to be more prone to adhesion by inflammatory cells, which can lead to complications such as lens deposits, synechiae formation, and reduced optical quality over time. Additionally, silicone IOLs are not compatible with certain diagnostic or therapeutic procedures, such as silicone oil tamponade used in retinal surgeries. For these reasons, acrylic materials—especially hydrophobic variants—remain the preferred choice for IOLs in uveitic eyes.

Single-Piece vs Multi-Piece

The structural design of the intraocular lens also plays a key role in postoperative stability and inflammation control. Single-piece IOLs, particularly those made from hydrophobic acrylic, are favoured for their simplicity and reliable performance in eyes affected by uveitis. These lenses have fewer points of mechanical interaction with surrounding ocular tissues, reducing the chance of irritation or friction-related inflammation. They are also more straightforward to implant and are less likely to shift or tilt postoperatively.

Monofocal single-piece lenses are especially recommended because they minimise optical aberrations and avoid the visual trade-offs associated with premium lens types. Multifocal or toric lenses, while beneficial for certain refractive needs, introduce multiple focal points that require excellent macular function to work well. In uveitic patients, where the macula may be compromised or at risk of future oedema, these lenses can result in suboptimal visual satisfaction and are therefore approached with caution.

Only in very select cases—where the uveitis has remained quiescent for a substantial duration, and retinal and macular structures are entirely healthy—might a surgeon consider implanting a premium IOL. Even then, it requires careful discussion with the patient about the potential risks and realistic outcomes. In most cases, the priority remains on inflammation control and surgical simplicity, which makes single-piece monofocal IOLs the safest and most practical option.

Consideration of IOL Placement

Intraocular lens placement is a critical factor that can influence long-term stability, inflammation risk, and visual quality in uveitic patients. Ideally, the IOL should be placed securely within the capsular bag, the natural envelope that held the original lens. In-the-bag placement provides the most stable environment and helps isolate the lens from other intraocular structures that could react adversely to a foreign material. This positioning also ensures a consistent visual axis and reduces the chance of lens tilt or decentration.

However, not all eyes present ideal conditions for in-the-bag implantation. In cases where the capsular bag is compromised—due to zonular weakness, capsular rupture, or fibrotic contraction—surgeons may need to consider sulcus placement. This involves positioning the IOL just behind the iris but outside the capsular bag. If this is necessary, special care must be taken to select an IOL that is specifically designed for sulcus use, typically one with appropriate haptic length and angulation to avoid iris chafing and subsequent inflammation.

Anterior chamber IOLs, which sit in front of the iris, are generally avoided in uveitic eyes unless no other option exists. These lenses have a higher profile and interact more directly with sensitive ocular tissues, increasing the likelihood of chronic inflammation, corneal decompensation, and secondary glaucoma. When forced into this route, surgeons must weigh the risks carefully and implement stringent postoperative monitoring to manage any emerging complications. Wherever possible, maintaining or recreating in-the-bag placement remains the gold standard for safety and visual outcomes.

Postoperative Monitoring and Management

The post-op period can make or break the surgical outcome in uveitic eyes. Even with a perfect surgery, inflammation can rebound aggressively if not managed carefully.

Aggressive Anti-Inflammatory Cover

Topical steroids are continued post-op, often at higher-than-usual frequencies. Some cases will require a slow taper over several weeks or even months. Systemic corticosteroids may also be continued, especially in cases of intermediate or posterior uveitis.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be added to help prevent CMO. Some protocols even recommend starting NSAIDs pre-op to build a baseline level of inflammation control.

Monitoring for Complications

Cystoid macular oedema is the most common sight-threatening complication post-op. OCT should be performed regularly to catch this early—particularly if there’s any unexplained drop in visual acuity. IOP should alsobe monitored closely, particularly in patients already at risk for steroid-induced ocular hypertension or those with a history of glaucoma.

Managing Rebound Inflammation

Despite best efforts, some patients will experience a flare of uveitis post-surgery. This is often managed with a temporary increase in topical and/or systemic steroids, or with additional intravitreal steroids. The key is acting quickly before any permanent damage sets in.

Long-Term Visual Outcomes: What the Data Says

So how do these patients actually fare in the long run?

Recent studies suggest that with proper control of inflammation, visual outcomes after cataract surgery in uveitic eyes can be comparable to those in non-uveitic cases. However, the presence of pre-existing macular damage, optic nerve involvement, or significant posterior segment disease does lower the ceiling.

A multicentre analysis published in the British Journal of Ophthalmology showed that over 75% of eyes with well-controlled anterior uveitis achieved 6/12 or better vision post-op. Outcomes were less predictable in posterior uveitis, reinforcing the importance of preoperative evaluation.

Infectious uveitis (like toxoplasmosis) presents unique challenges, particularly around timing of surgery and ensuring complete quiescence. Yet with careful co-management, even these patients can benefit substantially from cataract removal.

Special Considerations for Paediatric Uveitis

Children with uveitis—often linked to juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)—represent an especially high-risk group. These patients are prone to amblyopia, band keratopathy, and more aggressive inflammation. The decision to implant an IOL in a child with uveitis is always nuanced and must consider long-term growth and immune responses.

In many cases, the safer route may involve leaving the child aphakic (without an IOL) and correcting vision with contact lenses or spectacles until they are older. When IOL implantation is pursued, the same rules apply: acrylic material, in-the-bag placement, and maximal inflammation suppression.

Collaboration Is Key

Ultimately, cataract surgery in a uveitic eye isn’t a solo effort. It’s a team endeavour that often involves the cataract surgeon, a uveitis specialist, and sometimes even a rheumatologist. Coordinating care, ensuring consistency in treatment, and watching closely for red flags are all essential ingredients for success.

This is where shared care models and communication between specialties can truly shine. Patients benefit when clinicians take a unified approach that balances surgical precision with immunological expertise.

Final Thoughts

Cataract surgery in uveitic eyes isn’t for the faint-hearted—but it’s far from a lost cause. With good planning, clear communication, and evidence-based risk mitigation, patients can achieve meaningful improvements in vision and quality of life.

If you or someone you know is living with uveitis and facing cataract surgery, don’t let fear of complications delay the decision. Instead, look for a multidisciplinary team experienced in managing these complex cases. With the right care, your outcome can be just as successful as anyone else’s—just with a little more strategy involved.

If you would like to consult with a specialist cataract surgeon, you can get in touch with us here at the London Cataract Centre.

References

Bansal, R., Sharma, K., Gupta, A. and Gupta, V., 2015. Results of cataract surgery in patients with uveitis. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery, 41(5), pp.1016–1021.

Durrani, O.M., Tehrani, N.N., Marr, J.E., Moradi, P., Stavrou, P. and Murray, P.I., 2004. Degree, duration, and causes of visual loss in uveitis. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 88(9), pp.1159–1162. Available at: https://bjo.bmj.com/content/88/9/1159

Suresh, P.S., Jones, N.P., 2001. Clinical outcomes of phacoemulsification cataract surgery in patients with uveitis. Eye, 15(5), pp.621–625. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/eye2001185

Okhravi, N., Lightman, S., Towler, H.M.A., McCluskey, P. and Jones, N.P., 2007. Assessment of visual outcome after cataract surgery in patients with uveitis using the VF-14 index. Ophthalmology, 114(4), pp.816–821.

Bodaghi, B., Cassoux, N. and Wechsler, B., 2004. Chronic severe uveitis: etiology and visual outcome in 927 patients from a single center. Medicine (Baltimore), 83(6), pp.350–358.