If you’ve been diagnosed with thyroid eye disease (TED) and are also developing cataracts, you might be wondering how these two conditions interact—and more importantly, whether surgery can still be performed safely and effectively. The short answer is yes, but it requires a lot more planning, coordination, and expertise than standard cataract cases. That’s because TED changes the anatomy of your orbit, affects the way your eyes sit and move, and can increase the risk of complications during or after surgery if not managed properly.

In this article, we’ll walk through the key issues you need to know if you have both TED and cataracts. We’ll explore how proptosis can shift your visual axis, why dry eye is more than just a nuisance here, and how the timing of your surgery—whether you’re in the active or quiescent phase—can influence your outcome. So, let’s dive in.

Understanding Thyroid Eye Disease and Its Impact on Cataract Planning

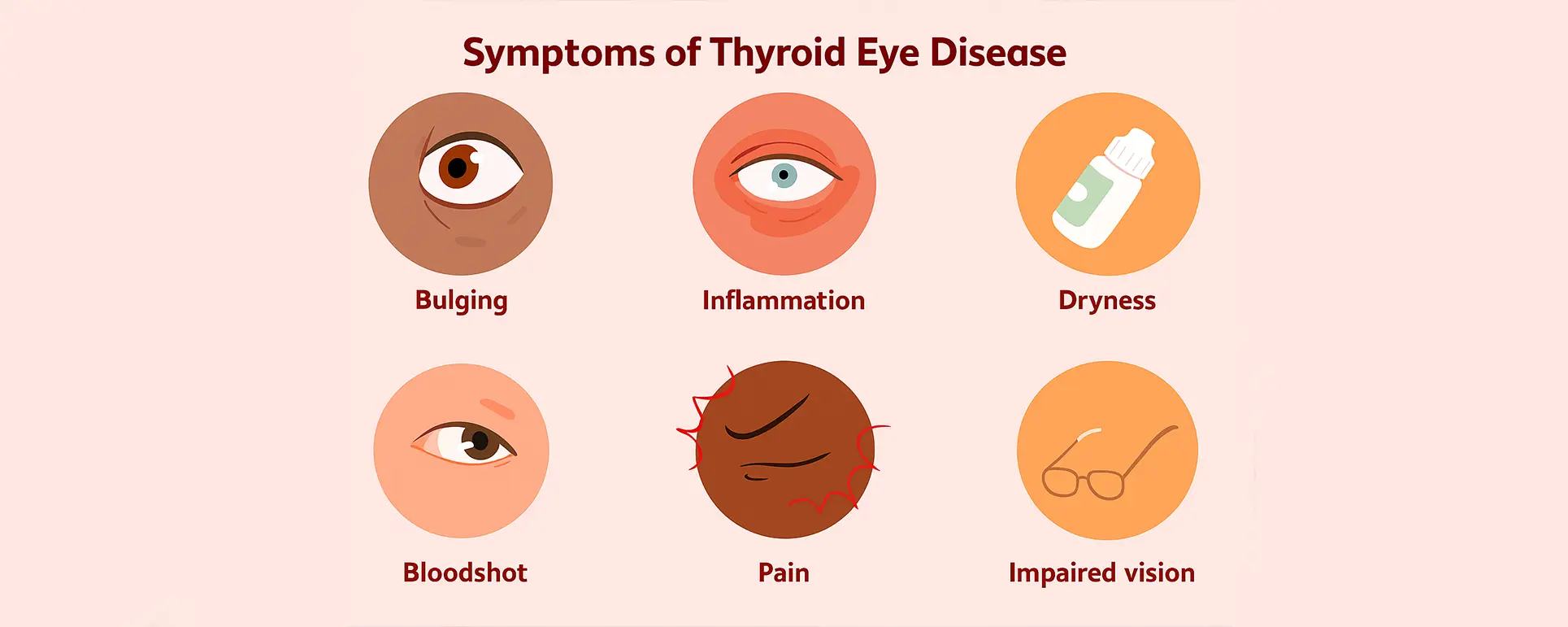

Thyroid eye disease, often linked to Graves’ disease, causes inflammation and tissue expansion within the orbit. The most visible feature is proptosis—where the eye bulges forward. But TED isn’t just a cosmetic problem. That forward displacement of the eye can alter how light enters the eye and can compress critical structures.

For cataract surgery, this anatomical shift has major implications. The eye is no longer in its ‘normal’ position, which means traditional surgical positioning might not line up the instruments properly. Visual axis alignment becomes a real challenge. And that’s before we even touch on intraocular lens (IOL) calculations, which rely on stable, centralised anatomy to be accurate.

On top of that, many people with TED also suffer from restrictive eye movements and eyelid retraction. These features can not only limit access during surgery but also raise the risk of corneal exposure, both during and after the procedure. And if you’ve had previous orbital decompression surgery, that’s another layer of complexity to factor in.

Why Proptosis Matters During Cataract Surgery

Proptosis doesn’t just make your eye look more prominent—it pushes the eye forward within the socket, sometimes dramatically. This can physically limit the surgeon’s view and access during cataract surgery, especially if the degree of forward displacement is high.

When the eye is protruding, the operating microscope’s focus may need to be adjusted extensively, and the surgeon’s ergonomics can be affected. In some cases, the use of a speculum or eyelid retraction may be inadequate because of the altered lid position. All of this contributes to increased intraoperative difficulty.

Another concern is the stability of the globe. Eyes with TED can be more mobile or unstable due to changes in the extraocular muscles. During surgery, this can translate into unpredictable eye movement unless properly stabilised, making precise phacoemulsification trickier.

Proptosis also alters the effective lens position (ELP), which can throw off IOL calculations. Biometry readings may not be as reliable, especially if there’s concurrent corneal irregularity or scarring from long-standing exposure or previous procedures.

Retrobulbar Pressure and Orbital Crowding

One of the more hidden dangers in TED is orbital crowding. The inflamed muscles and fat behind the eye take up more space than usual, leading to an increase in retrobulbar pressure. This pressure can affect the optic nerve and even cause compressive optic neuropathy in severe cases.

Why does this matter for cataract surgery? For starters, higher retrobulbar pressure makes the eye firmer—what surgeons call “tight”—which means there’s less give during surgery. This can lead to a shallower anterior chamber and greater difficulty in maintaining stability throughout the procedure.

Also, anaesthesia choices may be limited. In a normal eye, retrobulbar anaesthesia (an injection behind the globe) is commonly used. But in TED, that space is already tight, and adding more volume can increase pressure to unsafe levels, risking optic nerve damage. That’s why many surgeons prefer sub-Tenon’s or topical anaesthesia to avoid worsening the orbital pressure.

In more severe cases, orbital decompression may need to be done before cataract surgery just to relieve the pressure and give the eye more breathing room. This is particularly true if optic nerve compression is present or vision is already compromised.

Dry Eye in TED and Its Surgical Implications

Dry eye may sound like a minor issue, but in the context of TED and cataract surgery, it becomes a significant risk factor. Many patients with TED experience dry eye symptoms because of eyelid retraction, incomplete blinking, and corneal exposure.

Why is this a problem for cataract surgery? Firstly, poor tear film quality makes preoperative measurements like keratometry less reliable, which again affects IOL accuracy. Secondly, a dry and exposed cornea is more prone to injury during surgery. And thirdly, healing after surgery depends on a stable ocular surface—something many TED patients struggle with.

Managing dry eye aggressively before surgery is crucial. This often includes lubrication with artificial tears, punctal plugs, anti-inflammatory drops like cyclosporine, and sometimes even amniotic membrane treatment if there’s epithelial breakdown. Only once the ocular surface is stabilised should surgery go ahead.

Postoperatively, these patients also need close monitoring. Inflammation and dryness can flare, especially in cases where corticosteroids are used post-surgery to reduce intraocular inflammation, as these can further exacerbate surface issues.

Timing the Surgery: Active vs Quiescent Phase of TED

One of the biggest decisions in cataract surgery for TED patients is when to operate. Timing matters—a lot.

TED has an active (inflammatory) phase and a quiescent (stable) phase. During the active phase, inflammation is still progressing, and tissues are still changing. This phase is marked by swelling, redness, and often visual fluctuations. Operating during this time can be risky because things are still shifting—orbital pressure, corneal exposure, and even visual axis positioning are in flux.

That’s why surgery is almost always deferred until the quiescent phase unless vision is rapidly deteriorating and delaying the procedure would risk permanent loss. In the stable phase, tissue inflammation has plateaued, and measurements like axial length and keratometry become more predictable, which allows for better surgical planning and IOL accuracy.

If surgery must be done during the active phase—say, due to a visually significant cataract—then coordination with a multidisciplinary team becomes essential. This typically includes an ophthalmologist specialising in oculoplastics and possibly an endocrinologist to help stabilise thyroid function.

Selecting the Right Anaesthetic Technique

In TED patients, the choice of anaesthesia isn’t straightforward. Because of the increased retrobulbar pressure and potential for optic nerve compression, standard retrobulbar injections carry more risk than benefit.

Topical anaesthesia, often with a mild sedative, is the go-to for many surgeons. It avoids injecting fluid into an already crowded orbit and allows the patient to maintain eye position more naturally. However, topical alone may not be sufficient in more anxious patients or where prolonged surgical time is expected.

Sub-Tenon’s anaesthesia is a safer injectable alternative, providing a good compromise by numbing the eye without significantly raising orbital pressure. It also offers better akinesia (stillness) than topical alone. However, in patients with prior orbital decompression or altered orbital anatomy, even this approach needs careful handling.

Another trick up the sleeve for anaesthetists is peribulbar anaesthesia with reduced volume. It can offer sufficient anaesthesia without overfilling the orbit, but only in very controlled settings and in experienced hands.

Challenges with IOL Selection and Visual Axis Centring

Choosing the right intraocular lens (IOL) becomes more complex in TED patients. That’s partly because proptosis and orbital distortion can affect visual axis alignment and centration. Even a perfectly placed IOL may end up “functionally decentered” if the visual axis itself has shifted due to TED-related orbital changes.

For this reason, many surgeons avoid multifocal IOLs in TED patients, especially if alignment isn’t perfectly predictable. These lenses rely heavily on perfect centration and regular corneal shape, which TED patients may not consistently have.

Monofocal lenses, particularly with targeting for monovision or slight myopia, are safer and more forgiving. In cases where patients have significant astigmatism, toric IOLs can still be considered—but only after very careful corneal topography and visual axis mapping. Any corneal irregularity, scarring, or eyelid pressure-induced warping needs to be factored into the decision.

Adjustments to Surgical Technique in TED Patients

Performing cataract surgery in a patient with thyroid eye disease often requires slight—but significant—technical modifications. One common challenge is gaining access to the anterior chamber in a protruded eye. With proptosis, eyelid retraction, and limited eye rotation, the standard approach to incision may need to be adapted.

Surgeons may opt for slightly longer incisions or use different entry angles to accommodate the eye’s forward position. Holding the globe steady is also more difficult, especially when extraocular muscles are fibrotic or restricted. Fixation rings or gentle forceps stabilisation might be needed during phacoemulsification.

Because of these anatomical alterations, some surgeons prefer operating from a slightly modified head or body position relative to the patient, helping realign the instruments with the visual axis. These may seem like minor changes, but they can make a big difference in the comfort, control, and overall outcome of the procedure.

Additionally, a lower bottle height for fluidics and slower vacuum settings may be used to maintain chamber depth and avoid excessive turbulence in these more sensitive eyes.

Role of Oculoplastic Surgeons and Multidisciplinary Collaboration

Cataract surgery in TED patients is rarely a solo act. Ideally, your care will involve a multidisciplinary team that includes an oculoplastic surgeon—especially if your disease has required decompression surgery or if lid abnormalities are affecting corneal exposure.

The oculoplastic surgeon plays a key role in determining whether eyelid or orbital surgery is needed before cataract surgery. In some cases, orbital decompression is recommended first to reduce pressure and normalise the globe’s position. In others, eyelid repositioning might be scheduled after cataract surgery to improve postoperative corneal protection.

Endocrinologists are equally essential in ensuring that your thyroid hormone levels are stable. Even though TED is an autoimmune disease independent of thyroid function, unstable hormone levels can worsen inflammation and ocular symptoms. Achieving euthyroid status is a key prerequisite before proceeding with cataract surgery.

Postoperative Healing and Inflammation Management

Postoperative care in TED patients often requires closer and more extended follow-up than routine cataract patients. These eyes are more susceptible to inflammation, dryness, and surface instability—all of which can affect healing and visual recovery.

Anti-inflammatory drops, including corticosteroids and non-steroidals, are standard, but care must be taken not to exacerbate dry eye symptoms. In some cases, preservative-free formulations are used to reduce toxicity and surface disruption. Lubricating ointments may also be prescribed more generously post-op, especially at night, to protect the cornea while sleeping.

If you’ve had orbital decompression or lid surgery in the past, wound healing and swelling may follow a different course. Scar tissue, altered vascular supply, or lid retraction can contribute to prolonged inflammation or exposure risk. This makes it critical to attend all postoperative appointments so that complications like epithelial defects or delayed corneal healing are picked up early.

Finally, visual recovery might be slower in TED patients. It’s not uncommon for small amounts of residual strabismus or orbital asymmetry to affect perception initially, even with successful cataract removal. In such cases, prism glasses or referral for orthoptic evaluation may be beneficial.

What About Refractive Outcomes? Can TED Patients Expect Clear Vision?

Yes—but with caveats. While many TED patients do achieve excellent outcomes after cataract surgery, the path there can be more complex. The goal is to set realistic expectations and communicate that perfect vision may require a bit more work than in the average patient.

As mentioned, visual axis displacement, dry eye, corneal irregularity, and prior orbital surgery can all influence refractive accuracy. That’s why preoperative measurements must be done when the disease is stable and after ocular surface optimisation.

Furthermore, some patients might notice visual distortion due to concurrent strabismus or changes in binocular vision. These issues are usually managed with vision therapy or prisms but need to be discussed beforehand to avoid postoperative surprise or dissatisfaction.

Ultimately, successful cataract surgery in TED patients isn’t just about removing the cloudy lens—it’s about adapting the process to fit the unique challenges of your eyes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Is it safe to have cataract surgery with thyroid eye disease?

Yes, cataract surgery can be safely performed in patients with thyroid eye disease, but it must be timed carefully—ideally during the quiescent phase when the inflammation has stabilised. Surgeons also need to account for anatomical changes like proptosis, dry eye, and orbital tightness, which can affect both surgical access and recovery. - Will proptosis affect the outcome of my cataract surgery?

Proptosis, or eye bulging, can influence surgical positioning and the alignment of the visual axis, making surgery technically more complex. However, with preoperative planning and adjustments to technique, experienced surgeons can work around this and still achieve excellent visual outcomes. - Can I still have a multifocal lens implant if I have thyroid eye disease?

Multifocal lenses are usually not recommended in patients with significant thyroid eye disease because they rely on precise centration and clear optics, which can be disrupted by proptosis or corneal irregularity. Most surgeons prefer monofocal lenses for a more predictable result in these cases. - Does thyroid eye disease increase the risk of surgical complications?

Yes, TED can increase the risk of complications such as corneal exposure, dry eye flare-ups, and issues with wound healing, especially if surgery is performed during the active inflammatory phase. These risks can be significantly reduced with proper timing and preoperative management. - Is anaesthesia more risky in thyroid eye disease patients?

It can be. Retrobulbar anaesthesia, which is injected behind the eye, may increase orbital pressure in TED patients and is therefore often avoided. Safer alternatives include topical anaesthesia or a low-volume sub-Tenon’s block, depending on the complexity of the case. - Should I have orbital decompression before cataract surgery?

If you have severe proptosis or signs of optic nerve compression, orbital decompression surgery may be necessary before cataract removal to relieve pressure and improve eye positioning. Your oculoplastic surgeon will advise whether this is appropriate in your specific case. - Will I need additional treatments after cataract surgery?

Many TED patients do require ongoing dry eye treatment, and some may need eyelid procedures postoperatively to address exposure issues or restore corneal protection. These can usually be planned as staged treatments after your vision has stabilised. - How soon can I expect visual improvement after the surgery?

Most patients notice improvement in vision within a few days, although complete clarity may take longer if there’s dry eye, corneal damage, or residual alignment issues. The eye may also feel more irritated postoperatively, so close monitoring is important. - Will TED come back after my cataract surgery?

Cataract surgery itself does not reactivate thyroid eye disease, but any form of surgery can cause general stress on the body, which might unmask inflammation in rare cases. This is why TED should ideally be inactive at the time of surgery. - Can I avoid cataract surgery and just treat the thyroid eye disease?

Cataracts and thyroid eye disease are separate conditions. While TED can be managed with medication or surgery, a cataract that is affecting your vision won’t improve on its own and will still require cataract surgery at some point.

Final Thoughts: Where to Go from Here

If you have both cataracts and thyroid eye disease, you don’t need to feel overwhelmed—but you do need to choose a surgical team that understands the nuances of your condition. At the London Cataract Centre, we’ve managed many complex cases involving TED and tailor every step of the surgical journey—from biometry to anaesthesia choice to IOL selection—with these unique needs in mind.

Your surgery should not be rushed. Instead, it should be timed carefully, ideally in the quiescent phase of the disease, and approached with an understanding of the risks and anatomical changes that TED brings. With the right plan, you can absolutely regain clear vision and comfort, even with a history of thyroid eye disease.

References

- Dermarkarian, C. R., Grob, S. R. & Feldman, K. A., 2024. Acute vision threatening thyroid orbitopathy associated with cataract surgery: a case series and review of the literature. J Clin Res Ophthalmol, 11(1), pp. 011–016. Available at: https://www.clinsurggroup.us/articles/JCRO-11-205.php (clinsurggroup.us)

- Otah, T., Kumar, C. & Dodds, C., 2021. Sub‑Tenon’s anaesthesia for modern eye surgery—clinicians’ perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol, May 2021. PMID: 33536591. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8182827/ (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Sirr, C., Walsh, L., Doody, K. & Dillon, P., 2020. The choice of anaesthetic technique for cataract surgery. Mesentery Peritoneum, 4. DOI: 10.21037/map.2020.AB104. Available at: https://map.amegroups.org/article/view/5383/html (map.amegroups.org)

- Shakespeare, T. P., 2020. Anaesthesia for ophthalmic procedures in patients with thyroid eye disease. Eye, 34(4), pp. 1234–1242. Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0310057X20957018 (journals.sagepub.com)

- McKee, C., Strianese, D. et al., 2013. Unilateral proptosis in thyroid eye disease with subsequent contralateral involvement: retrospective follow‑up study. BMC Ophthalmol, 13:21. Available at: https://bmcophthalmol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2415-13-21 (bmcophthalmol.biomedcentral.com)