If you’re about to have cataract surgery, or you work in ophthalmology, chances are you’ve come across the term antibiotic prophylaxis. It’s one of the key strategies used to prevent postoperative endophthalmitis—an infection inside the eye that, although rare, can be devastating if it occurs. But here’s the big question: should antibiotics be delivered directly into the eye (intracamerally), or is using eye drops before and after surgery just as effective?

That debate has evolved significantly over the last decade. We’ve now got large-scale studies, updated national guidelines, and real-world data that shine a clearer light on which method offers better protection—and under what circumstances.

So let’s dive deep into both approaches, look at the evidence, and talk through what it really means for patient safety.

Why Antibiotic Prophylaxis Matters in Cataract Surgery

Cataract surgery is the most commonly performed operation worldwide. It’s typically a quick, safe, and highly successful procedure. But like any surgery, it carries a risk of complications—chief among them is postoperative endophthalmitis. While the incidence is low (roughly 0.03% to 0.2% globally), the outcome can be catastrophic, sometimes resulting in permanent vision loss or even complete blindness in the operated eye.

This is why antibiotic prophylaxis has become a central component of modern cataract surgery protocols. By reducing the bacterial load in and around the eye at the time of surgery, we can significantly lower the risk of infection.

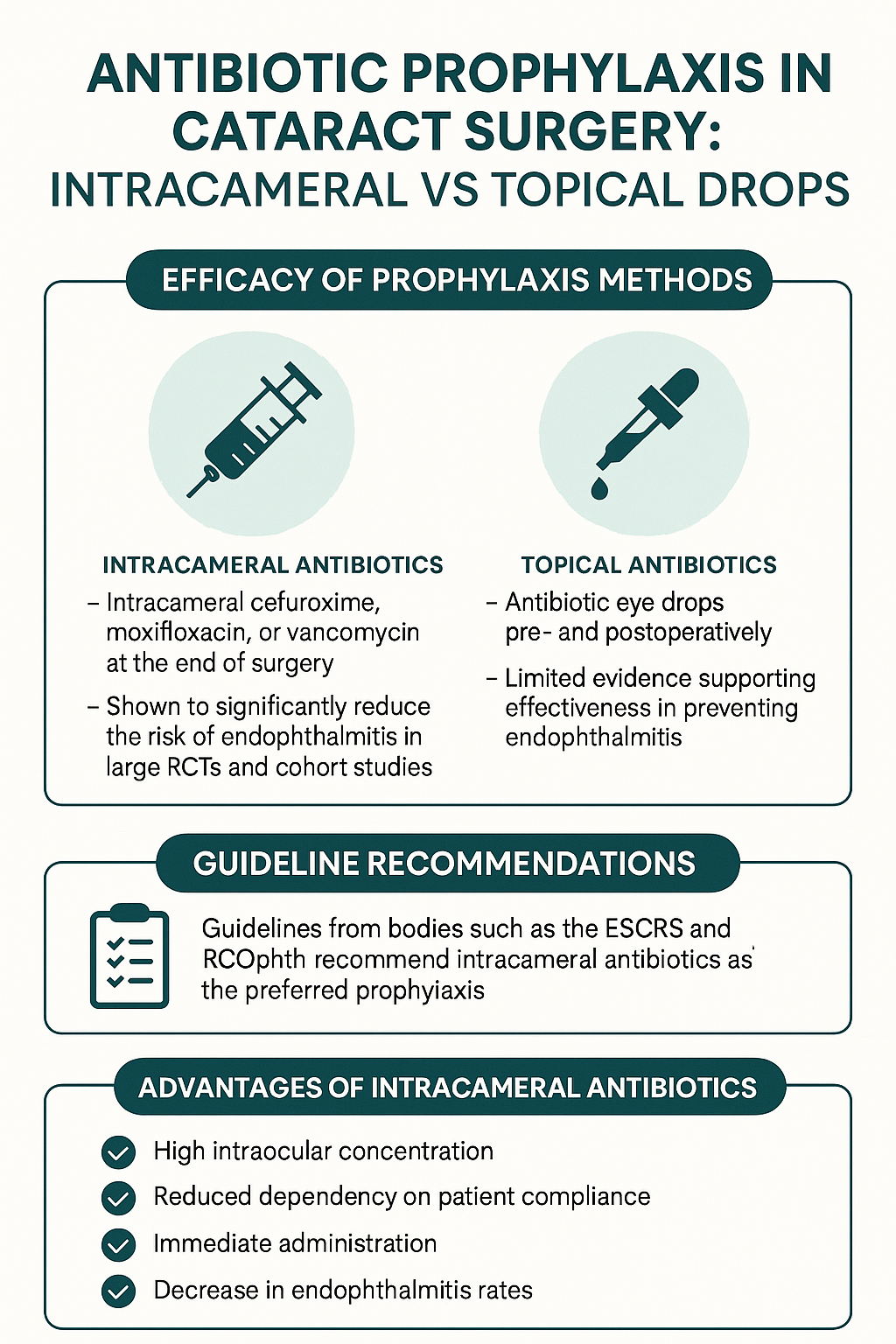

Historically, surgeons relied heavily on topical antibiotics before and after surgery. But in recent years, attention has shifted toward intracameral antibiotics—delivered directly into the anterior chamber of the eye at the end of the procedure. The theory is simple: deliver the drug right where it’s needed, in a single dose, and eliminate the need for patient compliance with eye drop regimens.

But how do the two strategies really compare?

Understanding Intracameral Antibiotics: What Are They?

Intracameral antibiotics are administered via a small injection into the anterior chamber of the eye at the close of surgery. This direct approach offers several key benefits.

Firstly, it bypasses issues of compliance. Some patients—especially the elderly—struggle to apply eye drops correctly and consistently after surgery. With intracameral delivery, you’ve guaranteed that the antibiotic is where it needs to be, at the right time, in the right concentration.

Secondly, the concentration of the drug in the eye is far higher than what’s achievable with topical application. This potentially improves its efficacy in killing or suppressing any bacteria introduced during the procedure.

The two most commonly used intracameral antibiotics are cefuroxime and moxifloxacin. Each comes with its own advantages, depending on patient allergies, local resistance patterns, and regulatory approvals.

Topical Drops: Still the Standard in Many Clinics

Despite the advantages of intracameral antibiotics, many ophthalmologists still prefer or supplement with topical antibiotics. These are usually prescribed for use a day or two before surgery, and then for a few days to weeks afterward.

Common choices include fluoroquinolones like ofloxacin or levofloxacin. The idea is to reduce surface bacterial load and prevent postoperative infection from microbes on the ocular surface or lids.

Topical drops are also non-invasive and familiar to patients. And in settings where intracameral drugs aren’t readily available or aren’t part of standard training, they remain the go-to option.

But here’s the challenge: their efficacy is heavily dependent on patient adherence. Forgetting doses, incorrect technique, or early discontinuation can seriously compromise their protective role.

What the Research Says: Intracameral vs Topical

Let’s now talk evidence. What do the large-scale studies and registry-based data say about these two methods?

The landmark ESCRS study (European Society of Cataract & Refractive Surgeons) published in 2007 was a game-changer. It involved over 16,000 patients across multiple centres and found that intracameral cefuroxime reduced the risk of postoperative endophthalmitis by nearly five-fold compared to no antibiotic prophylaxis. That’s a huge reduction in risk.

Since then, other observational cohort studies have reinforced these findings. For instance, a 2020 study from Sweden looked at over 600,000 cataract surgeries and concluded that intracameral antibiotics significantly reduced infection rates, regardless of whether topical antibiotics were also used.

On the flip side, no large study has shown topical drops alone to be more effective than intracameral injections. In fact, the vast majority of comparative studies suggest that intracameral prophylaxis provides superior protection.

That said, some data suggest that combining both methods may offer a slight incremental benefit, especially in high-risk populations (e.g., patients with blepharitis, diabetes, or immunosuppression).

Clinical Guidelines: Where Do They Stand?

Most modern clinical guidelines now endorse intracameral antibiotics as the preferred method of prophylaxis.

For example:

- The Royal College of Ophthalmologists (UK) recommends intracameral cefuroxime at the end of surgery as the gold standard.

- The American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) acknowledges the strong evidence for intracameral antibiotics and notes their growing use in the United States.

- The European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons (ESCRS) officially advocates for the use of intracameral cefuroxime as part of standard practice.

In contrast, the use of topical antibiotics is now often seen as supplementary. Some surgeons use them as an additional layer of safety, especially in patients with higher-than-average risk of infection or where intracameral agents are unavailable.

Pros and Cons of Each Approach

Here’s a breakdown of the pros and cons for each prophylactic method:

Intracameral Antibiotics

Pros:

- High intraocular drug concentration

- No reliance on patient adherence

- Immediate protection

- Backed by large RCTs and national guidelines

Cons:

- Requires careful dilution and preparation (risk of dilution error)

- Rare risk of toxicity (e.g., haemorrhagic occlusive retinal vasculitis with vancomycin)

- Not always available in ready-to-use format

- Some regional resistance concerns

Topical Drops

Pros:

- Familiar to patients and surgeons

- No intraocular manipulation required

- Widely available

- May be helpful in surface decontamination

Cons:

- Dependent on patient adherence

- Lower intraocular drug levels

- Delayed peak effectiveness

- Less effective as sole prophylaxis

Patient Safety and Real-World Considerations

From a patient’s perspective, safety is the priority. While intracameral antibiotics have a strong safety profile when prepared and administered correctly, errors in dilution or contamination can lead to serious complications.

There’s also the matter of informed consent. Patients should be aware of the type of antibiotic prophylaxis being used, the reasons behind the choice, and any potential risks.

In resource-limited settings or centres without access to pre-packaged intracameral drugs, topical prophylaxis remains a practical option. However, these centres are encouraged to explore affordable access to intracameral formulations, especially given the strength of the evidence in their favour.

The Role of Compounded and Commercial Intracameral Drugs

One of the challenges in broader adoption of intracameral prophylaxis has been drug availability. Compounded cefuroxime (e.g., from hospital pharmacies) was once the norm, but concerns about sterility and dilution accuracy raised safety alarms.

Today, commercially available preparations such as Aprokam (licensed cefuroxime intracameral injection) have improved safety and standardisation. Likewise, preservative-free moxifloxacin formulations (like Vigamox) are used off-label in some centres, especially where cefuroxime is contraindicated due to allergy.

Commercial preparations offer peace of mind for both surgeons and patients, but they come at a higher cost—a barrier for some institutions.

Are Combination Approaches Worth It?

Some surgeons opt for a belt-and-braces approach—using both intracameral and topical antibiotics. The idea is to eliminate any residual risk.

But the evidence supporting this strategy is mixed. While it may provide additional surface coverage, particularly in patients with chronic blepharitis or conjunctivitis, it also increases antibiotic exposure, cost, and the risk of resistance development.

It’s worth noting that indiscriminate use of antibiotics—especially fluoroquinolones—can lead to resistance. This is why some experts caution against routine post-op topical antibiotic use when intracameral delivery has already been administered.

Moving Towards Personalised Prophylaxis

Not all patients are the same. Factors like ocular surface disease, diabetes, previous ocular surgeries, and immunosuppression can influence infection risk. In the future, we may see more tailored prophylactic protocols based on individual risk stratification.

Artificial intelligence tools and big data analyses may help predict who is more vulnerable and guide more nuanced decisions about which prophylaxis method—or combination—is best.

What Surgeons Say: Insights from Clinical Practice

Surgeons who have adopted intracameral antibiotics as standard practice often report greater peace of mind. Many describe a noticeable drop in postoperative infections and fewer patient calls related to confusion or problems with drops.

However, for those new to intracameral delivery, training and guidance are essential. Proper preparation techniques, dosage knowledge, and aseptic handling protocols must be ingrained into practice.

Ultimately, surgeon experience, local protocols, and drug availability continue to play a big role in what method is used.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is endophthalmitis, and why is it such a concern after cataract surgery?

Endophthalmitis is a rare but serious infection inside the eye, usually occurring after eye surgery. When it follows cataract surgery, it’s known as postoperative endophthalmitis. The infection typically involves the aqueous or vitreous humour and is most often caused by bacteria entering the eye during or after the operation. If not treated swiftly and aggressively, it can result in permanent vision loss or even the complete loss of the eye.

While the incidence is very low—especially with modern sterile techniques and antibiotic use—the consequences can be severe enough to make prevention a top priority. In fact, even a single case can lead to significant medico-legal challenges for the operating surgeon or surgical centre. It’s a complication that every ophthalmologist takes seriously.

The good news is that most cases are preventable. Careful sterilisation, surgical draping, and the use of prophylactic antibiotics have brought the risk down to a fraction of what it was decades ago. However, no method is foolproof, which is why the conversation about the best type of antibiotic prophylaxis—topical versus intracameral—is still very much ongoing.

If you’re a patient preparing for cataract surgery, it’s helpful to know that your surgeon will be taking steps to protect you from this infection. Knowing what those steps are and how they work can make you feel more confident going into the procedure.

2. How do intracameral antibiotics work, and are they safe?

Intracameral antibiotics are injected directly into the anterior chamber of the eye at the end of surgery. This means the antibiotic is delivered straight to where it’s needed—inside the eye—at a high concentration that topical drops can’t achieve. The goal is to kill any bacteria that might have entered the eye during the procedure before they have a chance to multiply.

The two most common drugs used are cefuroxime and moxifloxacin. Cefuroxime is often the first choice, backed by strong evidence from European studies. Moxifloxacin is sometimes used as an alternative, especially for patients with penicillin or cephalosporin allergies. These antibiotics are usually diluted to a safe concentration and prepared in a sterile environment, either in theatre or supplied as a ready-made solution.

When prepared and administered correctly, intracameral antibiotics are considered very safe. However, errors in dilution or the use of contaminated solutions can cause serious problems, including toxicity or intraocular inflammation. That’s why many clinics now prefer commercially available preparations like Aprokam (for cefuroxime), which help reduce human error.

Overall, intracameral delivery offers powerful protection with a low risk of complications—especially when best practices are followed. It’s not just about convenience; it’s about delivering effective infection control in the most direct and efficient way possible.

3. Why are some surgeons still using topical drops instead?

Topical antibiotics are still widely used because they’re familiar, non-invasive, and relatively inexpensive. Many surgeons and patients feel comfortable with them, and in some countries, topical drops remain part of the standard pre- and post-op care. They’re particularly common in places where intracameral antibiotics haven’t yet been fully adopted due to supply, cost, or regulatory issues.

Some eye units also choose to use both topical and intracameral antibiotics as a combined approach. The rationale is that topical drops reduce the surface bacteria on the conjunctiva and lids, while intracameral antibiotics target bacteria inside the eye itself. This ‘belt and braces’ method may provide an extra layer of safety, especially for patients at higher risk of infection.

That said, relying solely on topical drops has some drawbacks. Their effectiveness depends heavily on patient compliance. If the patient forgets doses, applies the drops incorrectly, or stops too early, the intended protection is weakened. Studies have consistently shown that topical-only prophylaxis is less effective at preventing endophthalmitis than intracameral antibiotics.

So while topical drops haven’t disappeared from practice, they’re no longer considered the gold standard on their own. In many high-volume surgical centres, they’ve been replaced—or at least supplemented—by intracameral injections based on the overwhelming evidence of greater efficacy.

4. What do the major studies and guidelines recommend?

The strongest piece of evidence comes from the ESCRS randomised trial published in 2007, which found that intracameral cefuroxime significantly reduced the rate of endophthalmitis compared to topical drops alone. That study changed practice across Europe and led many surgeons to adopt intracameral antibiotics as standard.

More recent observational studies involving hundreds of thousands of cataract surgeries have continued to support those findings. For example, large registry data from Sweden, the Netherlands, and the UK all show lower infection rates when intracameral prophylaxis is used. Some studies also found no additional benefit in combining it with topical drops, though others suggest a modest improvement in certain high-risk groups.

Professional guidelines reflect this evidence. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists in the UK recommends intracameral cefuroxime at the end of surgery. The American Academy of Ophthalmology also supports its use and has published guidance on safe preparation and administration. Similarly, the ESCRS now considers it best practice for all cataract surgeries.

The growing consensus is clear: intracameral antibiotics offer the most effective protection against endophthalmitis. That doesn’t mean topical drops are obsolete, but their role has shifted more towards being supplementary rather than essential.

5. Can patients request one method over another?

Yes, patients can and should be involved in decisions about their surgical care—including how infection prevention is managed. If you’re having cataract surgery, you’re well within your rights to ask your surgeon what type of antibiotic prophylaxis they use and why.

Most surgeons will follow a protocol based on national guidelines and the resources available in their clinic. If the standard is intracameral injection, they’ll explain how it works and why it’s used. If topical drops are being prescribed instead, they should provide guidance on how to apply them correctly and stress the importance of following the schedule exactly as instructed.

In some cases—such as patients with drug allergies or specific medical conditions—a customised approach may be necessary. For example, someone allergic to cefuroxime may be offered moxifloxacin or another suitable alternative. Likewise, some patients may still be given topical drops post-op, even after an intracameral injection, if their individual risk profile warrants it.

The key is open communication. If you have questions or concerns, bring them up before the operation. Understanding the ‘why’ behind your prophylaxis plan helps build trust and ensures you’re part of the decision-making process.

Final Thoughts: Which One Should You Go For?

If you’re preparing for cataract surgery or advising patients about their options, the evidence is clear: intracameral antibiotics—especially cefuroxime—offer the most effective prophylaxis against postoperative endophthalmitis.

That doesn’t mean topical drops are obsolete. In certain settings and for certain patients, they remain useful. But as far as primary protection goes, the data consistently favours intracameral injection.

And if you’re running a clinic or managing theatre protocols, now is a great time to review your prophylaxis policies. Are they up to date? Are staff trained on intracameral delivery? Are commercial preparations available?

The goal is simple: safer surgery, better outcomes, and peace of mind for both surgeons and patients.

References

- European Society of Cataract & Refractive Surgeons (ESCRS), 2007. Prophylaxis of postoperative endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: results of the ESCRS multicenter study and identification of risk factors. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, 33(6), pp.978–988.

- Friling, E., Montan, P., Johansson, B., Behndig, A., Zetterström, C., Stenevi, U. and Lundström, M., 2013. Six-year incidence of endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: Swedish national study. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, 39(1), pp.15–21. Available at: https://www.jcrsjournal.org/article/S0886-3350(12)01494-4/fulltext

- Haripriya, A., Chang, D.F. and Namburar, S., 2019. Endophthalmitis reduction with intracameral moxifloxacin prophylaxis: analysis of 600,000 surgeries. Ophthalmology, 126(6), pp.768–775.

- Royal College of Ophthalmologists, 2021. Guidelines for the Prophylaxis of Endophthalmitis Following Cataract Surgery. London: RCOphth.

- Barry, P., 2014. ESCRS Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Endophthalmitis Following Cataract Surgery: Data, Dilemmas and Conclusions. ESCRS EuroTimes, 19(6). doi:10.1038/eye.2013.276